Addressing the Opioid Epidemic

This year we passed lifesaving legislation to combat the opioid crisis here in Connecticut. We will soon have one of the most comprehensive laws in the nation to prevent and treat opioid abuse. It is important to understand what led us to pass this groundbreaking legislation. From now until International Overdose Awareness Day on August 31st we will be taking an in-depth look at the opioid epidemic in Connecticut as well as our efforts to address it.

Where we stand now

On average two people in Connecticut die from drug overdoses every day. More people die in Connecticut from drug overdoses than in car accidents or by gun violence. The 723 drug overdose deaths in 2015 were more than twice the number three years ago.

Of the 723 overdose deaths in 2015, more than 60 percent involved opioids. Most notably: Heroin, Fentanyl, Morphine, and Oxycodone, as well as brand name pills such as OxyContin, Percocet, Vicodin, and Demerol.

How did we get here?

The Opioid epidemic has hit every state in the country. We can trace the huge increase in overdoses in part back to 2001 when the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations requiring hospitals and health care facilities to ask about pain as the fifth vital sign, along with pulse, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, and temperature. No doctor wants their patients in pain but we know that pain level isn’t an objective vital sign. Nonetheless the quality of pain treatment became one of the metrics by which hospitals were evaluated. As a result doctors began writing prescriptions opioids much more frequently.

However, surveys have shown that those that who use opioids non-medically don't typically get them from doctors or prescriptions but rather they are given pills by a relative or a friend with leftover medication from a prescription.

In 2013 we implemented a prescription-monitoring program to address overdoses from prescription drugs. Tightening control on prescription painkillers, however, drives some people abusing pills to switch to heroin and fentanyl both of which are more potent, cheaper and far more available. Fentanyl alone is 50 to 100 times more potent than heroin.

From 2014 to 2015, the number of times fentanyl was found in the bloodstream of overdose victims increased 150 percent, and last year it was responsible for one quarter of all drug overdoses. Meanwhile deaths involving heroin more than doubled from 2012 to 2015.

But how do these drugs work? How do they affect the body and what can we do to reverse their effects?

How opioid overdoses occur

State Representative Theresa Conroy explains how opioids effect the body and how opioid antagonists like Narcan work to reverse those effects. This year we passed legislation that requires municipalities to equip their first responders with an opioid antagonist such as Naloxone which is sold under the brandname Narcan. Earlier this week Governor Malloy thanked the Connecticut state police for saving 100 lives utilizing overdose reversal medication.

In this short video you can see how to assemble and deliver a syringe of naloxone nasal spray.

Demographics and geography

Between 2012 and 2014 (the only years for which we have complete overdose data) we see a widening gap between white death rates and the death rates for other racial and ethnic groups.

More than half (56 percent) of opioid overdose victims who died between January 2012 and September 2015 were aged 40 or older. Heroin was the most common cause of death for those between the ages of 21 and 45 while hydrocodone, oxymorphone, and oxycodone were more common among those older than 45. The older people get, the more often they visit doctors and accumulate supply of prescription medications.

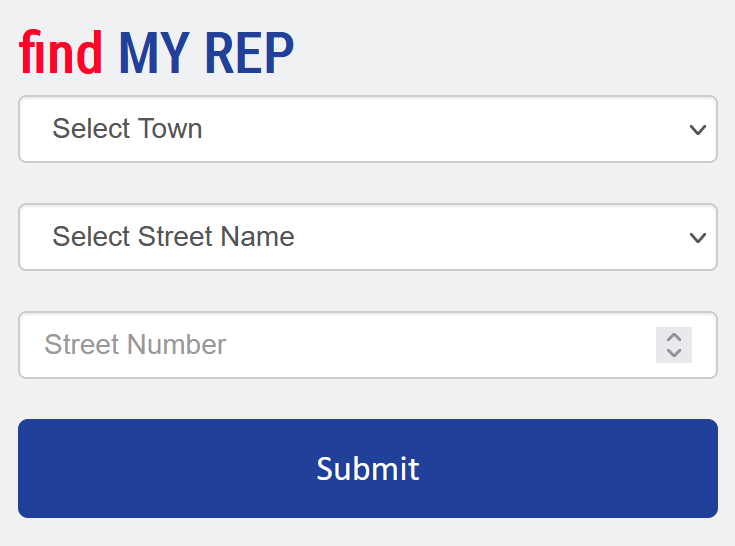

Since 2012 Waterbury, Hartford, and New Haven have traded spots among the top three towns with the most drug overdose deaths. This isn’t too surprising since those are three of the largest cities in Connecticut. However, when we look at death rate per 10,000 residents, North Canaan (7 deaths) and Sprague (6 deaths) jump to the top of the list. In smaller towns a handful of deaths can throw off per capita calculations but the impact is felt by the entire community. The reporters at Trend CT put together an interesting map that looks at the drug overdose rate by town over the last few years.

We took the same data Trend CT analyzed and looked at drug overdoses that specifically involved opioids. From 2012 to 2015 the number of deaths in Connecticut associated with heroin alone more than doubled. This graphic compares the city of residence for every opioid related death in Connecticut in 2012 and 2015.

Navigation: Select the "visiable layers" button to toggle between 2012 and 2015 data. Source: Office of the Chief Medical Examiner via CT Open DataVictims with no known city of residence or victims who resided out of state were not included in this graphic. Data-points are not representative of specific addresses

When you look at this data it become clear that overdosing in a small town carries a higher risk of death. That is why this year we passed legislation to equip all first responders with Naxolone (sold under the brand name Narcan), a drug made to revive someone from an opioid overdose. This way, even small towns with fewer resources will be able to combat opioid overdoses.

Capping opioid prescriptions

The opioid- heroin prevention bill we passed this year included many measures aimed at reducing overdoses and addiction. In the video below State Representative Matt Ritter explains one aspect of the bill which caps opioid prescriptions at 7 days. This limit is important because 55% of people who become addicted to opioids get their first dose from a friend with medicine left over from an old prescription. Furthermore according to the American Association of Addiction Medicine four of every five new heroin users comes to the drug from prescription opioids. Our hope is that this new cap will help eliminate a potential gateway to addiction.

International Overdose Awareness Day

Over the next few years we will do everything we can to combat this crisis. However, before we take any action we want to make sure we know what works best that is why Governor Malloy has asked Dr. David Fiellin and a team of doctors who are addiction specialists from Yale School of Medicine to create a strategy to reduce opioid addiction and overdoses. Meanwhile, state representatives such as Theresa Conroy (Beacon Falls, Derby, Seymour) have been leading community forms in their districts.